To Daddy (yes, I sometimes still call him that)

John Michael Owens is my father. I’ve never seen him feign a smile, he’s just not that kind of guy. You know when he is enjoying himself because his cheeks get red and he wears an expression of laughter. He’ll look around with this face, sometimes holding a beer in one hand, and its as if he’s soaking up something great.

When I go to mass with my father, he prays, hard, and I can see it in his face. As everyone kneels, he takes his head in his hands and stays that way until the priest asks us to rise again. When I asked him about it he told me he goes for my mother and because he likes to take the time to think about his life and our lives.

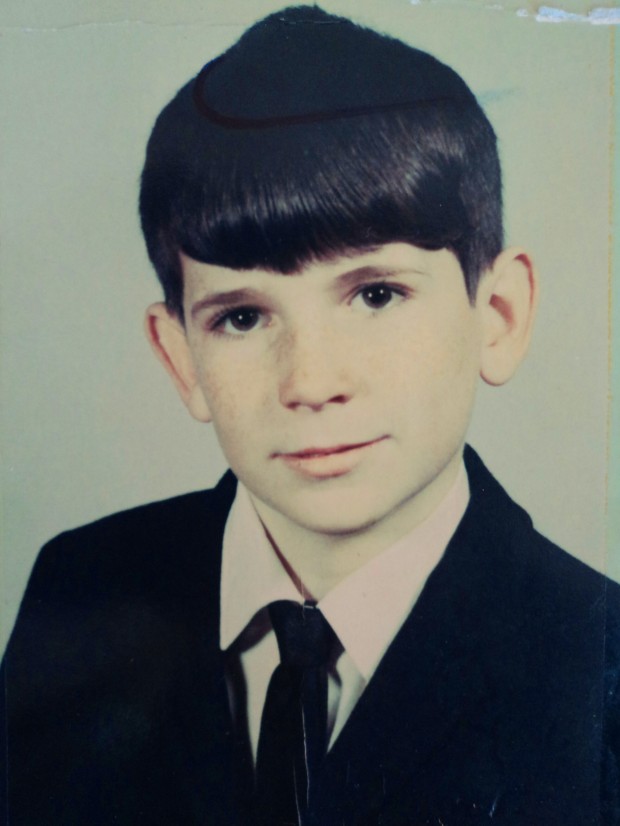

My dad was born in 1955 and I’ve always imagined him as a boy like Kevin Arnold from the Wonder Years, a thick head of black hair, mussed up from football with his brothers or setting off cherry bombs with old pal Hal Wenzel in the creek behind his house in Mission Hills, Kansas. Kitchen was closed between meals so he and my Aunt Janet got in the habit of grabbing handfuls of sliced bread, molding it into balls with their hands and eating it as a snack. My Aunt Janet explained this to me recently after years of witnessing my father pass through the kitchen for a handful of sliced bread. That’s my dad. I love that some things never change.

When I was ten years old, I would bring home graded assignments and hand them over to my father. With a half-serious face he’d look me in the eye and say, “another one bites the dust,” as if to suggest my grade was the triumphant end of a zero-sum game. He made A’s special this way. He wasn’t proud of me, he was betting on me and he liked his odds. I always wanted to win for him and bring home anything that warranted his best Queen impersonation.

To scare us or make us laugh, I’m not sure which one, he used to flip his eye lid inside out. Just one eye lid. It was enough to send me into a fit. He would just stand there grinning with one eye. Because I am grown now, he wastes no time pulling this trick on any of his young nieces and nephews. They love it.

On Christmas morning, after an hour of little fingers poking at his tummy from the bedside, he would agree to wake up and come downstairs to begin present opening. Always in his red and green striped robe and Santa hat, he was responsible for passing out the gifts one by one. As the master of ceremonies, he would announce each name on the package after drum rolls and long silences looking around the room, tension mounting and all of us squirming and trying to suppress shrieks of excitement. “And this one is for………..CO…CO!” He would draw out our names mimicking the drama of a baritone opera singer. And I’m writing about it now as if he didn’t do the same thing this year.

My father makes the best damn chili I’ve ever had in my life. It is incredible. Whatever chili you are thinking about right now that might top his is no where near as good as my father’s chili. I am serious about this. He has won chili contests. He makes it twice a year, both times in the winter, once on the super bowl and again on a very cold and gray day of his choosing.

My father institutionalized what we call in my family “grill time.” In the back yard, he sits one lawn chair beside his own and invites one child to join him. It is a rite of passage, really, to be in the company of his prized grill and smoker, to be handed a Boulevard and asked to stay for a while. Usually, he’s philosophizes. For each child, there is a different subject matter. For Sean, the military and other masculine subjects he couldn’t pursue as easily with his daughters. For Shelley, his godson, tales of nursing and her wicked ways as an older sister. For Mary, it’s law and basketball. For me, its history, academics and “the Coco world,” as he calls it. If he’s feeling sentimental, he’ll try to slip a little mathematics into the conversation. This may need explaining. My father, more than anything, wanted a little math genius for a daughter. Poor guy got a writer instead. But even so, I used to talk math with him. He wanted to teach me about game theory and string theory and why am I sharing this information? We can be seriously nerdy people sometimes. I eventually communicated to him, around age thirteen, that I wasn’t interested. But after another beer and the steaks almost done, he’ll tell me about what math book he’s been reading before bed and I listen though I like talking history with him best.

There is one story in my home everyone can equally recall due to the memory of searing, side-splitting laughter. In a McDonald’s parking lot at the tail end of a long road trip through the windy plains of Oklahoma, my father had pulled over to throw away empty bags from lunch. We watched him – moody – from our seats, weary from road squabbles and restless legs. From the vacuumed silence of our car, straight ahead we saw him approach a dumpster. On any other day less windy or any other parking lot, perhaps, the trash he threw into the air would have landed in the receptacle but as it just so happened, the little trash bags he released with good intention came to life in the air and swooped down and around him. Within seconds, the wrappers flew out of the bags, adding to the windstorm with my father in the center of it, arms flying in great effort to collect what had escaped. It seems this struggle between my father and the wind trash continued for quite some time. When he returned to the car we were in tears from laughing so hard. Without even trying, he had lifted our mood indefinitely through the end of our family road trip.

There is one story in my home everyone can equally recall due to the memory of searing, side-splitting laughter. In a McDonald’s parking lot at the tail end of a long road trip through the windy plains of Oklahoma, my father had pulled over to throw away empty bags from lunch. We watched him – moody – from our seats, weary from road squabbles and restless legs. From the vacuumed silence of our car, straight ahead we saw him approach a dumpster. On any other day less windy or any other parking lot, perhaps, the trash he threw into the air would have landed in the receptacle but as it just so happened, the little trash bags he released with good intention came to life in the air and swooped down and around him. Within seconds, the wrappers flew out of the bags, adding to the windstorm with my father in the center of it, arms flying in great effort to collect what had escaped. It seems this struggle between my father and the wind trash continued for quite some time. When he returned to the car we were in tears from laughing so hard. Without even trying, he had lifted our mood indefinitely through the end of our family road trip.

And he’s always played that role – the man of a family built on memories he made for us.

Imagine,

And some Dads only got Diamonds or Gold for fathers day.

this is adorable….. my favorite part is getting to sit next to him while he cooks the chili. i totally understand the feeling. 🙂 miss you!!!

You’re a great writer,

your life’s idyllisms remind me of Dan In Real Life, pure Americana.

lovely